In 2012, the media focused on the comments of an economist, Shamubeel Eaqub, who is well documented for being anti-property. Bear in mind the media likes to present two sides to a story, in this case the counter point in the property debate. So Mr Eaqub fits the ticket for anything related to property bashing.

Of note was this economist's claim that owning property as a family home in New Zealand does not make sense, that you are better to rent houses and invest your home equity in the stock exchange. I found this information counter intuitive in relation to the property I routinely get involved with, so crunched the numbers.

Shamubeel Eaqub

To be fair, in a 2014 reader poll (by The Visible Hand in Economics), Mr Eaqub was voted the fourth sexiest economist in New Zealand – I take my hat off to him. However, I don't think he will ever be the richest economist, based on his statement that the ownership of houses is bad business. He called buying a house a 'loss-making business' and recommended that people invest their money in the share market instead. I have many self-made multi-millionaires as clients who made their money in buying residential property. In fact one of my staff members just made his second million (in equity), buying houses in Auckland. He just turned 30. I don't think owning your own home or rental investments is a bad business, but let's take a closer look.

Overview of analysis: Sell your home/Rent and put your money in shares

I did the maths on five houses in Auckland and a few down country. The table below shows what they look like with 50% finance and capital growth rates that are representative of the areas these properties are in, versus renting them. I calculate where you are if you own the houses and get capital growth, versus using the extra cash you would have if you rented and invested the surplus (including the starting equity from selling the house) into shares at a 5% after tax return.

- Note that the first five properties are from all corners of Auckland at all levels, and renting loses every time.

- The sixth and seventh properties are in smaller cities (Hamilton and Rotorua) with lower growth.

- Renting wins (over ownership) on financial grounds in very low growth environments. Having used a 2% growth rate for Rotorua, renting would make sense if the growth is that low. However, it would not take too much more capital growth for ownership to make sense in this small town as well. Take a look at the numbers reading top down:

I know people may raise their eyebrows over my capital growth rate assumptions at 7.5%–9% for Auckland houses, but let's face it, Auckland has a land supply problem. It is not solved in the short to medium term by the Auckland Unitary Plan, as there are significant lead times to getting the services in the ground and the rules in place to bring land supply on tap. I acknowledge that projected growth rates are subjective and affect the above analysis, but further note that if you change the capital growth rates to say 6%, ownership still wins.

A few more points of contention are:

- I assume interest-only loans. You could argue that the owner will be locking up more cash as they pay down the loan, but that won't change the story.

- Cost inflation runs at about 3% and rental inflation at around 2%. As rents are greater than operating expenses (generally rent is 4–5 times OPEX), if you inflate these items, this further supports ownership as rents increase more than opex overall, in gross dollar terms.

- I assume you pick a low maintenance house. I'm not talking about owning run-down villas, or run-down old weatherboard houses. I'm assuming you make an intelligent choice of home and start with a renovated property in my maintenance assumptions.

- I note that my assumptions are based on direct observation of my clients' portfolios, and my own portfolio of 20+ residential properties (mostly in Auckland.) I'm not making up the OPEX – these numbers come out of analysing my own property assets and those of thousands of clients that my firm acts for.

- So when people tell me it costs tens of thousands in maintenance to own a home, I say you need to distinguish renovation and upgrades from basic maintenance to keep a house in working order. If you start with a renovated low maintenance property, my assumptions are good. If you start with a run-down villa that needs to be re-clad, re-reroofed, re-wired, re-insulated, re-plumbed, etc., you are not starting with a renovated property so that's an unfair argument and comparison.

- This analysis assumes you borrow 50%, which is probably invalid for most households as they will be more or less indebted depending on the household situation. Interestingly the more the debt, the more the benefit because you are getting leverage on the capital growth at a rate exceeding the after tax return from the shares.

Discussion of analysis

To explain the analysis (if the spreadsheet does not make sense):

- First I calculate the cost of ownership if you buy a house and keep it for 10 years. Note, I deduct projected capital growth to reveal the cost of ownership after taking into account projected house price inflation. I don't sell the house at the end so there are no real estate fees, but even if I did, it would not change the story.

- To be fair, I am using capital growth rates of 7.5%–9% straight line which have been valid long terms trends in Auckland for at least 30 years. Rates assumed are lower for Rotorua and Hamilton. As said, these numbers are subjective and are my opinion of indicative future returns in these areas, based on past performance that I have taken from REINZ stats. (But of course the growth is not guaranteed, it is projected. And to state the obvious, past performance does not guarantee future performance.) These rates could decline as asset values rise, but then with Auckland's housing shortage I don't see much chance of that any time soon.

- Note I have used a high average interest rate assumption of 7%, not current GFC rates which are prevailing at lower averages. This makes my maths harder, not easier, to say property ownership is better. If I reduce the cost of ownership by reducing the interest rate to say 6.25%, then the story is even more commandingly in favour of ownership.

- After looking at the full cost of ownership net of capital growth, I then calculate the cost of renting, and assume that the spare cash that comes from not owning is invested at 5% (after tax) and compounded with a fund manager. I assume no entry or exit cost with the manager. Therefore, the real cost of renting is rent paid over 10 years, less the return on the money saved (and invested) by not owning.

- As a point, I think it is a poor assumption that the surplus would be saved, because most Kiwis (if they rented) would probably spend the surplus and therefore end up poorer at the end.

- However, for the purposes of the argument I assume we have a perfectly disciplined investor who diligently saves the surplus and invests it at 5.0% after tax.

- It must be noted, however, that if we are talking about the 'business of property ownership', then the commercial observation that Mr Eaqub is missing is that home ownership not only makes sense mathematically, it is commercially good for Kiwis to have their cash locked up in their homes as a forced savings scheme.

- In addition, profits on dividends are taxed. The capital growth on houses is not taxed. This gives home ownership another obvious advantage, coupled with the benefit of bank leverage. It is leverage at good growth rates, plus a better tax profile on the capital profits, that really stand the property ownership model up as a winner.

- As said, I've used an after tax rate of return of 5% on surplus funds available if you rent. You can debate what that number should be until the cows come home, but the point is unleveraged returns in shares versus leveraged capital growth on property is not a fair fight. The average Kiwi is carrying debt on their home and therefore they are getting the benefit of leverage in the capital growth they are receiving that you don't get if you sell your home and put your money in the share market. If you are unleveraged, the story might be a bit different.

Sell your home, rent and tip the surplus into shares

I am guessing that Mr Eaqub also aggregates all property as a giant average, in making the sweeping statement that 'owning a house is bad business'. If he said 'owning a house in a low growth area is bad business', I might agree. But in the context of Auckland, Canterbury and other better capital growth areas, I think his advice reveals yet another economist talking in averages that are not reflective of regional variances in capital growth rates.

Moreover, many economists who provide commentary on property make the assumption that the population is average, they invest in averages and get the average outcome. This is overly simplistic, because it assumes you are not smart enough to do the maths and work out where you can get above average capital growth in property. For example, a home owner can beat the market average by buying subdivisible property (e.g. buy something that is being rezoned under the Auckland Unitary Plan to get better growth rates – I have been buying heaps of these properties for my own portfolio because it is obvious these assets will jump in value when the new zoning rules come in). In summary, dealing in averages ignores your ability to add value to the returns gained through home ownership by being intelligent in your choice of property and picking the better assets.

So I say:

- In main centres where growth rates are expected to be high (areas that I advocate investors and home owners stick to), ownership by far wins out over renting and investing the surplus in shares.

- In small town New Zealand where growth rates are likely to be low, of course ownership is not about financial advantage, it is more about the emotional security of having a cheap roof over your head, which you can renovate and call home. But it is still not a bad business; it is very comparable to shares as the example above for Rotorua reveals. And I would say if we are talking about home ownership in the context of a business, the forced disciple of a principal and interest loan is not an unhealthy business practice.

- Mr Eaqub ignores the benefit of leverage (as I expand on below). If you invest $100,000 in shares, you get a return on $100,000. If you leverage at 80% LVR in property investment or through home ownership, you get a capital return on $500,000.

- I can play with the numbers and fiddle the analysis to make it look more marginal or more attractive, but I genuinely believe that if people own assets in land-starved areas with good fundamentals (think Auckland), the growth on their home will cause them to be ahead over renting in the long term. They will also get the commercial benefit of being forced to effectively save (by funding ownership, to later have the money refunded on sale through capital growth).

- OK, a risk of the argument is that capital growth rates fall or interest rates go higher than the 7% average forecast. I think these risks can be managed with fixed rate agreements and picking your areas carefully. Moreover these risks also exist for shares.

- I say again, I disagree with commentators who use averages as projected returns, when discussing direct investment in property. Averages assume everyone is equal and gets the average of the market – not true when it comes to property. The average is the aggregate of good and bad results mixed together. It's very misleading and a misinformed analysis in my view.

- Direct investment in property is therefore less comparable to an indexed fund in this regard. You can use your brain and your brawn, buy the better assets in the better areas, add value to them, and make money on the way into a property (renovation etc.) – which eclipses the average returns. If my property investment portfolio was built on averages, I would be broke. Average houses in Auckland are cash flow negative. Mine are cash flow positive when I buy them. I balance cash flow with capital growth assets, and target niches. I buy subdivisible or rezoned land (for higher growth). I don’t invest in ‘average houses in average suburbs getting average yields’. The same argument extends to home ownership. You can beat the average by buying smart, and commentators should not assume that home owners are not smart enough to make informed choices.Shares vs property: Is property investment bad business?

Shares vs property: Is property investment bad business?

Let’s look at a second argument that arises from Mr Eaqub’s property bashing stance. He has said that you are better to sell your home and invest your equity in the stock market. This pre-supposes that the stock market beats property investment. More particularly, property investment is normally leveraged, so he presupposes that the stock market beats leveraged property investment.

In short, I wonder why Mr Eaqub does not suggest instead as a more balanced view to ‘sell your home if it is in a low growth area, and buy a mix of leveraged property investment in high growth areas and some shares’. This would result in a more diversified return and provide the benefit of leveraged high growth property assets for part of the return. Most authorised financial advisers I have met take this approach when advising my firm’s clients in financial planning engagements.

The benefit of leverage

Take the following example showing identical returns between property and shares as a hypothetical analysis. Recall that to compare two investments, you should be thinking about the total return derived from the different asset classes (i.e. the after tax cash flow added to the capital growth).

- In the case of property: Total Return = Net Revenue + Capital Growth

- In the case of shares: Total Return = Dividend + Capital Growth

For argument’s sake, let’s look at these and assume a similar rate of return, given that the markets are perfectly competitive and over time the returns should be similar. (Economic theory would say capital will chase higher returns and compete away any supernormal profits to equalise/normalise returns over time.)

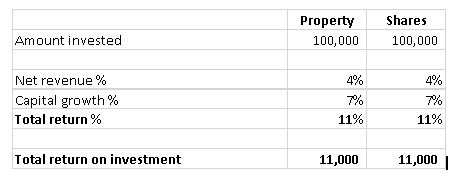

Unleveraged investment, hypothetical identical return assumption

But people generally use 80% leverage in their residential property investment. Now let’s look at the returns with the costs of leverage and benefit of capital growth factored in.

As you can see, investing the same amount ($100,000) on identical returns (which I have made up for argument’s sake), provides a very different result with leverage applied to property. Property wins hands down.

- You end up with $199,600 more by buying property and leveraging at 80% LVR, after taking into account deficit cash flow (after tax) on the stated assumptions.

- Projected property equity is double the equity you would get from unleveraged investing in shares.

- Granted, you will have the risk of the leverage in property, and you will have the ups and downs of the property cycle. But you earn twice as much for your risk, and that aside, shares and the share market carry their own risks.

- I would also comment that when it comes to the shares versus property argument, many people I meet prefer to be in control of a physical asset (property), rather than relying on the performance of company CEOs and the fund managers picking or indexing stocks. This is part of the Kiwi psyche and love affair with property, rightly or wrongly.

- The key to negatively geared property is getting the capital growth. It is essential to invest a leveraged property portfolio in areas with good fundamentals, as not all property has equal prospects for capital growth or revenue returns. Weighted against that, the share market story requires you to pick the right shares with the best fundamentals, so this part of the risk is the same – you have to pick winning property and winning stocks.

Leverage in the share market?

Of course for devil’s advocate, we might say you can leverage shares. I would reply firstly that this is much riskier due to the propensity to have a rapid market movement in the stock market and margin call by a bank (on the leveraged shortfall). Secondly, leverage offered by New Zealand bankers tends to be limited to 50% on lower risk shares, reducing leverage and restricting yield to that derived from blue chip stock. Thirdly, you end up with interest/cash flow issues on most stocks (as many will not pay a dividend and instead retain earnings), making the investment extremely cash flow negative if you leverage it (until you sell). I hope that makes sense.

Comment on growth prospects

Right throughout the GFC I encouraged clients to focus property investment in the Auckland property market (and I continue to do so). The yield averages cited by various commentators (on Auckland yields) assume the investor is uninformed and buying on averages. I don’t know many investors who are this uninformed to be frank – it seems the investors know more about the topic that the commentators here.

Parochial investors in small towns are less likely to be rewarded in the long run with good growth. With the exception of Canterbury and maybe Hamilton and Wellington, the smaller cities and provinces just don’t have the fundamentals that support a commanding capital growth story in my view. I prefer areas with tight supply, sustainable demand and high incomes to support a growth environment. Call me a Jafa, but the winner will always be Auckland in a capital growth contest in NZ.

Summary

- While the return on shares may equal property over the long term (in a perfectly competitive environment), the benefit of leverage means in the ‘property versus shares’ argument, property wins. Take the leverage out of the argument and it’s a fair fight, but few people own property unleveraged.

- It is much better to own property if you buy it in areas with high capital growth. Less so in low growth areas, Mr Eaqub.

- The benefit of leverage coupled with untaxed gains on home capital growth, gives home ownership an advantage over share investing.

- Owning your family home in low growth towns is of questionable financial benefit (it’s more even – not particularly tipped one way or the other in my numbers). But then most people want the benefit of being able to have a secure home environment (from which they cannot be evicted by a landlord) and to be able to make renovations to suit their own purposes. Can we put a number on this as part of the analysis of ‘is home ownership a bad business’? I think so, and whatever the number, it tips the balance of the argument in favour of home ownership, even in low growth environments.

I therefore conclude owning your home is a good business to be in.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. This article is generic discussion and should not be construed as financial advice.

Matthew Gilligan

Managing Director and Property Services Partner

Did you like this article? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive tips, updates and useful information to help you protect your assets and grow your net worth. We're expert accountants providing expert advice to clients in NZ and around the world.

Disclaimer: This article is intended to provide only a summary of the issues associated with the topics covered. It does not purport to be comprehensive nor to provide specific advice. No person should act in reliance on any statement contained within this article without first obtaining specific professional advice. If you require any further information or advice on any matter covered within this article, please contact the author.

Comments

Testimonials

I got a lot out of each Property School session and feel I have a lot more knowledge. - Amelia, September 2018

Gilligan Rowe and Associates is a chartered accounting firm specialising in property, asset planning, legal structures, taxation and compliance.

We help new, small and medium property investors become long-term successful investors through our education programmes and property portfolio planning advice. With our deep knowledge and experience, we have assisted hundreds of clients build wealth through property investment.

Learn More